In 2019, we start our Fablab Residency program! If you're an artist, designer, engineer or developer and want to develop a new creative project with our digital manufacturing machines, Fablab.iMAL can offer you a residency!

Interested? More here.

Pierre Lavoie was the CEO and creative director of Hyptique, one of a handful of multimedia studios that defined interactive culture in France from 1994 to 2005. Hyptique has directed a large part of the cultural production of that decade and has also published a number of titles under its name, mostly in the field of music. Pierre Lavoie was the founder of the Numer non profit organization in 2000, introducing the term interactive design in France and making happen the meeting of tens of international designers with a very large public. He sold Hyptique in 2011 and is currently consultant on digital issues for major culture role players.

What made you want to join the of CD-Rom industry?

After being an art dealer and a linguist, which led me (through artificial intelligence) to computer science and graphic user interfaces, I saw multimedia materialize right in the middle of my fields of interest: culture and interactivity. I went up to the major French publishers to demonstrate that I understood their language perfectly and that I could translate it into computer language. Within a year I found myself with a team of 15 employees and a small army of freelancers.

My impressions is that I did not deliberately choose a direction but rather followed the wave. I was not the only one: you'd find typically architects, writers, scientists and journalists at the head of a "multimedia studio." They all had a multidisciplinary background that prepared them for this redefinition all creative trades, and everyone was trying to invent those new skills with people who, obviously, had not been trained for that – we did not talk much about this methodology issue but it was very important, it fascinated me as a manager, and digital practices today still bear the mark of this origin.

Did you consider the CD-Rom as a new medium or as new media? Was there something like "CD-Rom art"?

Technically the CD-Rom leans more towards a medium. It was a new device for transporting data, that until then we could only move with a hard drive. As a means of transport, it allowed the development of a market – and afterwards also caused its decline. In this view, "CD-Rom art" may have borne a contextual meaning, related to trends and expressions of that time – but no etymological reality. It may be more relevant to talk about the days of the CD-Rom.

In fact the real medium, the blank page, is the computer. The computer is the environment that makes it possible to specify the algorithmic object that is the program which, when its purpose is to deliver some form of word, (using text and/or images and/or sounds) was then called multimedia. If we're looking for a media in the McLuhanian sense, it's probably this: a program with more or less the same function as literature, film, music, etc.

How can we complain about the difficulty to exhume and decipher the artifacts of ancient cultures and at the same time consciously (or even conscientiously) keep burying our computer creations as fast as we produce them? It's time to talk about auto-archeology.

What are the new opportunities offered by the CD-Rom for content creators?

The computer is similar to paper: it is a medium that can be used to make calculations, write texts, invoices, shopping lists, contracts or to create scores, draw plans, illustrations, advertisements, comics... The only difference is time: the representation on paper is static while what one confides to the computer takes place in time (a corollary of the famous Turing theorem). It transforms itself, and the specification of this transformation is part of the writing process – it's the algorithm, which can generate a potentially infinite number of distinct sequences. These sequences of transformations are selected in a nonlinear flow through interactivity.

It is this totally new phenomenon of nonlinear intellectual creation that the computer made available to creators. The advent of the CD-Rom opened up this new discipline to a selected public and that fueled its early growth even though it was stopped in infancy.

Has the CD-Rom really been a "revolution" or was it simply a medium for reconciling pre-existing forms?

The real revolution is the computer. Just like the invention of writing did 5000 years ago by introducing a plastic and persistent representation of our thoughts, the computer leverages our cognitive performance by letting us manipulate transformations of this representation. From then on we can undertake the complexity of dynamic behavior that was completely out of reach beforehand.

Until now there was prehistory, separated from history by the discovery of writing. This chapter is now closed: we will call it "predigital history" and history, here and now, will be implicitly digital

The befriending of the computer by creators (writers, directors, designers, ...) is one of the critical milestones of this evolution. It happened relatively early in the history of computing, but we had to wait for the democratization of image and sound on ordinary computers (circa 1990) and the possibility to transport large volumes of data (the CD-Rom), before production processes and a corresponding market emerged.

Therefore, it's clear that CD-Rom titles reproducing pre-existing forms took no advantage of the new medium that was the computer. On the contrary, those who made use of new IT potentials differed clearly from all other forms of anterior expression. At the same time, it was always about telling a story, using primarily traditional media that was, however, organized in totally new ways, subject to new constraints as well as unprecedented digital processing. In short, each discipline redefined itself, yielding objects at once familiar and surprising, fascinating for many.

What was the CD-Rom that made you want to get started? Which one impressed you the most?

Many of the first titles were interesting – especially the pioneering production of Voyager. Xplora1 by Peter Gabriel, too, has helped us a lot as an example of the media quality we could aim for. It's interesting how the technical constraints of the time (HyperCard, Videoworks...), which were so much heavier and inescapable then today, induced a powerful creativity and products of great originality.

Like all my colleagues, I was inluenced by some significant titles for our profession: Circus, Puppet Motel, Freak Show, and later Alphabet, Isabel, etc. But we ourselves were CD-Rom players from the very beginning and, within the scope of the projects that came to us we were always trying to position ourselves at the forefront of innovation – with titles like Au cirque avec Seurat, Carton, Proust, Yves Saint-Laurent, La Musique Électroacoustique, etc. and even works for children like Ça se transforme, Tom-Tom et Nana, Passeport, etc. for which we had the opportunity to invent a new publishing trend.

Personally, I have always been less impressed by technological cleverness and cool graphic effects then by the relevance of the interactive structure. This type of useful innovation often goes unnoticed – indeed, its vocation is to remain invisible to the user.

What were the main challenges for the "democratisation" of contents?

On a big CD-Rom monograph the first pitfall was the interactive scenario. Our clients for example, which were large respectable French publishing houses, usually advocated a kind of interactive maze where the reader/user could choose their own route. They asked us to structure the corpus of the subject and to make sure one could browse in all directions. Result: you'd find lots of answers... to questions you'd never think of. It was deadly. We quickly realized that, instead of delivering an editorial DIY package, we needed to speak up, offer a point of view. Therefore, we decided to develop systematically a linear throughway with a video but interactive narrative to which the user could relate, revealing to him the mystery and complexity of the subject. Once awaken to this, he could then evolve on his own between the dynamic surface of the discourse and its factual, more static foundations.

Then there were technical difficulties. The computers were limited, the CD-Rom drives rather slow ... We had to deal with all that. For example, the screens (at the beginning) could only display 256 colors – to compare: all computers today display millions of colors. It's impossible to make an acceptable color gradation with only 256 colors. This constraint imposed long and laborious optimization tasks and limited graphic design tremendously. The low bandwidth of CD-Rom drives and the many bugs of the authoring tools made our lives even more complicated.

The third and maybe biggest challenge was methodological: how to have writers, editors, graphic designers, musicians, computer animators and developers converge in a collaborative dynamics towards a published product that's high quality and technically reliable, while controlling deadlines and costs, knowing that it was impossible to have a perfectly clear idea of the project before its completion? It was great art.

There was also an important financial constraint. The pressing was expensive, the distribution was sometimes holding more than 60% of the wholesale price, the retailer kept a huge margin to itself... Consequently we needed to sell a (too) large number of titles in order to pay off the costs of production – but we were the production costs. On this issue also we had to be resourceful, optimizing budget leverage on one side, and having the publisher fall for our tantalizing promises on the other.

I think that the study of our first achievements can bring to new players a better understanding of the possibilities. Knowledge of the classics is essential for contemporary creators.

How do you analyze the failure of the medium a posteriori?

We experienced this failure in real time – we had it coming for a while. Unlike other media, the CD-Rom did not really score strong points on any level: it required a sedentary reading station (not like a book), entailed major technical issues (complicated installation, available resources, bugs...), was very expensive without providing the possibility to try it before buying (unlike music) and did not provide a shareable experience (like a concert or a movie).

But video games, also on CD-Rom, had exactly the same shortcomings. However, they had the advantage of a content based on the pleasure of playing – as opposed to the joy of culture... It is true that the products were not always fascinating. The market has collapsed before the discipline matured – except for youth titles, a market that prevailed until the tablet took over.

But time will tell. We experienced this first failure over a few years that taught us a great deal. Internet has not (yet) been able to take over, for obvious monetization difficulties. The interactive word is still as legitimate as ever and it will eventually emerge by itself.

What are the legacies of these CD-Rom experiments?

The media don't need us to hybridize. Today we do a lot of reading on digital pads, in formats (ePub, among others) that offer easy integration of interactivity, video, music... These multimedia options will not stay unnoticed much longer: literary works will soon have sound and animation (some already have). What will we call them? I don't know, and it's perhaps the end of literature as we know it, but I'm especially curious to see how they will necessarily delinearize as they become interactive...

Anyway, I think that the study of our first achievements can bring to new players a better understanding of the possibilities. Knowledge of the classics is essential for contemporary creators (artists, designers,...) – in that way multimedia is not different from the traditional disciplines.

According to you, why should we preserve this content? In what capacity and in which form?

First of all, we have written the first pages of a story that, as measured to the human adventure, has just begun. As always, the past will give meaning to the present – we will therefore need access to it in order to understand and structure creation. Or simply to avoid repeating history without knowing it, as can be witnessed today.

But from a more general stand point, how can we complain about the difficulty to exhume and decipher the artifacts of ancient cultures and at the same time consciously (or even conscientiously) keep burying our computer creations as fast as we produce them? It's time to talk about auto-archeology.

It should certainly be interesting to look into the first few seconds of the technocultural big bang, when intellectual discourse collided with the digital and its nonlinear implications. What happened at the time determined orientations that, as of today, still condition our interactive practices.

Finally there is an ecology in this rehabilitation process. Sustainability is not only for energy and biodiversity issues: skills also have value, and costs, and they can become extinct very easily.

Interview by Marie Lechner, journalist specialised in digital cultures, and researcher at Pamal (Preservation-Archeology-Media art Lab) at the École Supérieure d'Art in Avignon (pamal.org)

A historical selection of art & culture cd-roms and electronic artworks published on floppies, mostly produced in the 90s highlighting the short life of born-digital art. It presents early pioneering works in new media and digital arts, conveying many visions and utopias around the upcoming digital world as well as remarkable explorations of interactive digital media.

WELCOME TO THE FUTURE

- Visions, Utopias & Politics

- New Art Forms

- Documenting Contemporary Art

- Digital Heritage

- All interviews

In 2019, we start our Fablab Residency program! If you're an artist, designer, engineer or developer and want to develop a new creative project with our digital manufacturing machines, Fablab.iMAL can offer you a residency!

Interested? More here.

In the context of Transmediale festival in Berlin, Wallonia Brussels International organises an exhibition showing pieces by 3 Brussels-based artists: Felix Luque, Julien Maire and LAb[au].

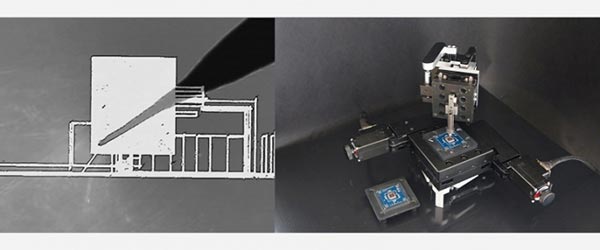

iMAL is very happy to be associated with this event as the co-producers of Julien's new work Composite as well as Felix's installations D.W.I. and Memory Lane.

Signals:...

The time has finally come: our renovation works at 30 Quai des Charbonnages started last week! After some demolition works, we can start building up our new, 3-storey centre for thedigital art and culture, which will open autumn 2019. Follow us on instagram,...

This page is an archive of the iMAL website that operated between 2010 and 2019. It compiles activities and projects made since 1999.

For our most recent news and activities, please check our new website at https://imal.org

asbl iMAL vzw - 30 Quai des Charbonnages Koolmijnenkaai 30 - 1080 Bruxelles Brussel 1080 - 32 (0)2 410 30 93